It was long ago when I learned, while in the company of a Navajo elder in the Arizona desert, about the “vision of the eagle”. We were sitting by the shadow of the “great rock” and the elder was patiently listening to my disquisition about the thinking of the indigenous people of my country; suddenly his eyes were fixated on an eagle that was flying above our heads. He looked at me and started saying: The vision of the eagle is one that all the beings that inhabit this earth share. When the eagle is up, it is looking at an immense territory, so immense that we could not encompass it all. It sees it all, even the smallest thing with all of its details. Suddenly, a rabbit hopped and the Eagle, flying so high, feels it run in the grass, it fixates on it, it looks at the field, it feels the wind, and calculates how both, rabbit and wind, can run on the sinuosities of the ground. It takes all things into account, so many things that I cannot enumerate them. All of a sudden it throws itself into the void, as into death, as fast as an arrow. It comes down rapidly and when one thinks it is going to crash, it turns in the air and captures its prey. Everything happens instantly and precisely. One second, ten centimeters, and the eagle would be wounded or dead. But instead, it elevates back into air with the rabbit in its claws. This action is so precise because the eagle, up there, can see it all in its totality, with each detail, like threads that are weaved to make up the reality of the world, of the here and now. That is the vision of the eagle, when one can understand the whole interweaving, then one can touch every stitch and every thread, and one’s decisions are accurate.

The Andean vision of water is embedded in the “vision of the eagle”. Water is never seen as a separate element, but as a living being that forms part of the weaving of life within the community of nature, which the Kechuas call Sallka. Therefore, water is one of the constituent beings of the territory, together with human beings and the community of deities. It is family and it builds, together with the other two communities, through a mutual upbringing, relating through dialogue, reciprocity, and complementarity.

The cosmovision -vision of the eagle- is, for the three communities -deities, nature, and human beings-, the larger context, the nucleus, the axis of all way of living, the indication of how to be in this world. One is in this world to be, and not, like us, the westerners, to exist. This is the vision that was and is shared by almost all the native peoples of the Ancient America since it was the Abya Yala “fertile land surrounded by water”.

This cosmovision, represented in the Law of Origin of each nation, it is its referrer of relationship, of duties and rights, of significance and meaning; is expressed through myth and it becomes operative through rite, which is both celebration and festivity. The cosmovision expands and enhances, like waves of water in a lake, successive waves that contain it and through which we denominate thought and culture.

When the cosmovision is transformed into Law of Origin, it is done because it is in direct relation with a territory that includes the community of the sacred, the community of nature, and the human community, Waka, Sallka and Runa in Andean Kechua. This Law of Origin guides the wise people of a human community to do thinking with the purpose of shedding light, from this great law, to the issues of the community. For this reason, in Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, called “the Heart of the World”, the Mamos or spiritual wise people of the four nations –Kogis, Arhuacos, Kankuamos and Wiwas-, guardians of the four corners and the four elements of this heart -earth, fire, air, and water- gather at the kankúrwa or “sacred house” to light the four fires and sit at the center with the Mamo to dedicate themselves to “do thinking” recreating their Law of Origin to solve concrete problems of their time at this world.

When the cosmovision is transformed into Law of Origin, it is done because it is in direct relation with a territory that includes the community of the sacred, the community of nature, and the human community, Waka, Sallka and Runa in Andean Kechua. This Law of Origin guides the wise people of a human community to do thinking with the purpose of shedding light, from this great law, to the issues of the community. For this reason, in Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, called “the Heart of the World”, the Mamos or spiritual wise people of the four nations –Kogis, Arhuacos, Kankuamos and Wiwas-, guardians of the four corners and the four elements of this heart -earth, fire, air, and water- gather at the kankúrwa or “sacred house” to light the four fires and sit at the center with the Mamo to dedicate themselves to “do thinking” recreating their Law of Origin to solve concrete problems of their time at this world.

But both cosmovision and thought need to materialize into actions of re-creation of the world in the apparent reality, what is established in the field of culture, which is doing in the world from the action that recreates the thought. All that is perceptible by the external senses is culture expressed in shape. Culture is a way of the doing of all living beings, not only the human being. Therefore, water, a part of this intertwined weaving in its deepest part, has life, forms part of the cosmovision, generates thought, and has culture.

That said, the main issue in this process and the fundamental difference between the native world and the mestizo world, is the coherence with which the cosmovision, the thought, and the culture are intertwined. If any action in the world accurately reflects a thought, which at the same time reflects a cosmovision, this doing is coherent and harmonious. If on the contrary, as it happens in the mestizo world that was imposed five hundred years ago, the culture as action does not recreate the world, but it tries to dominate it, to control it, to use and possess it cumulatively; this cultural action denies or overrides the thinking and thus, the cosmovision. The results are clearly visible. This brings us to a fundamental question: What is in essence being an indigenous person? There is one answer to that question: real respect to a Law of Origin and coherence, respecting this law, its form of being in this world. This is the path to becoming a human being from the indigenous point of view.

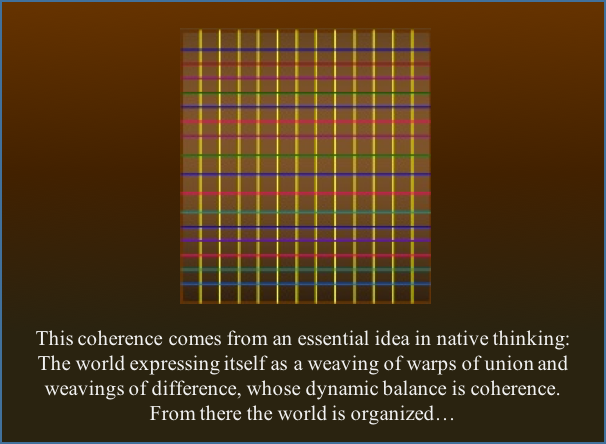

The world is structured in this way, from a mother cosmovision, which can be pictured as a woven-world: The loom which reflects the four parts of the world and its four corners, where warps of relationship and different weavings are woven. The warp is the diachronic and synchronous cosmovision shared by the native peoples from their population, allowing a deep relationship: the weavings, which begin when each cosmovision generates specific thoughts, are given in the amazing diversity of the peoples and their cultures, when these inhabit territories that are distinct because of their position and climate.

It is not by chance that in the vision of the Kogi of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia, the territory is considered a great loom that has its borders where the sacred hills and main rivers which descend from the sacred snow-capped peaks to the ocean, the mother of all waters. The weaving is done when the living beings transit the paths that cross the territory both vertically, between different ecologic grounds, warps, in which inter-Andean valleys interweave horizontally, forming the weavings of territorial and cultural diversity. It is in this sacred geography where relationships between the sacred, the territory, and culture have been woven. The ancient Tayronas, ancestors of the four current native peoples, built their urbanism and architecture in stone and water, one of the most interesting organic designs that is known in America. For this reason one of the main concerns of the Mamos or sacred authorities of these peoples is the way in which the “younger brother” the mestizos and white people of the other culture, are handling the water, conceived in simple terms as a resource to be used, barely considering it as a weaving when it is viewed in terms of water basins.

Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta has at least thirty-five of these great basins that belong to the Caribbean Sea slope. The most serious problem is that the basins show severe environmental effects, losing almost 49% of its runoff in less than twenty years, affecting the supply of fresh drinking water not only for the indigenous people of the Sierra, but for important urban centers such as the three capitals of this area of the country: Valledupar at Cesar, Santa Marta at Magdalena and Riohacha at Guajira.

A similar case occurs in one of the most important American wetlands, located in the North-West of what is now Colombia, known as the Momposina depression, more than 500.000 hectares of wetlands, which make up sort of the “kidney” of the Colombian territory. It is at the Momposina depression, known as the “Mojana”, where three great Colombian rivers pour their sediments: Magdalena, Cauca, and San Jorge, arriving already purified to their mouth in the Caribbean Sea. For around 1.500 years the Zenú native people sustainably managed this territory, maintaining its balance, in one of the most interesting cases of hydraulic engineering in native America. Today the descendants of these indigenous people are desperately fighting to obtain drinking water. For the last twenty years, our poor management of the wetland ecosystem nearly brought about the collapse of it, destroying the natural system and its recreation accomplished by the Zenú. The Zenú continue to think of water as a living being, with whom one needs to converse and reciprocate under other principles.

Cycle of water in the Andean way of thinking:

Water is life, cosmovision, thought, culture, and the connecting path between the seeds of the sacred, nature, and human beings.

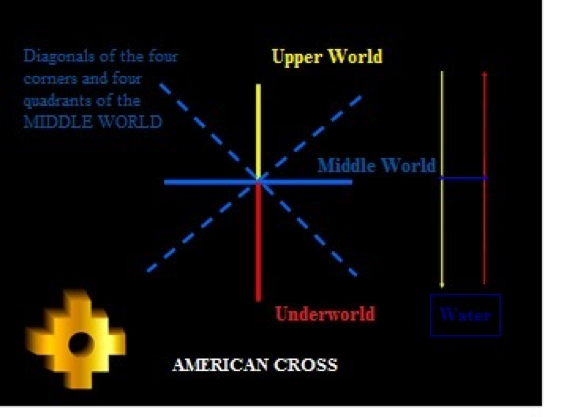

The water dwells as a sky-blue seed in the Upper World (Hanan Pacha), within the River of the Sky, the Milky way, from where, imprinted by solar semen, it descends in the shape of a cloud to condense over the earth; from there it falls in the form of water-weaving in the shape of rain until it arrives to the skin of the mother; it penetrates her entering the uterus-Underworld (Ucku Pacha), where it fertilizes the seeds of all life achieving its various forms; once fertilized, the seeds in “our mother, our father”, emerge through the subterraneous waters of the Middle World (Kay Pacha) where they are expressed as the three basic communities: deities (Waka), nature (Sallka) and human beings (Runa).

Each of these communities–Waka, Sallka and Runa-, inhabitants of the Middle World in which we all exist, have a dual nature: they are female and male at the same time, with different levels of manifestation, either predominantly female or predominantly male. All the process of life, which we denominate humanization, as a vital experience, seeks to accomplish complementarity of these two principles until they achieve harmony as everything else. For this reason, the three communities establish a type of relationship that we can denominate conversation, reciprocity, and complementarity. All three are incomplete, even the deities, they need one another. This completeness begins with a conversation that is established through aware observance and the way of knowing, which is actually a way of remembering.

Conversing is listening to the other through every sense and letting our voice be heard not from a position of authority, but as an exemplary expression, of self-experience, which serves only as an example to be considered; one converses with the sacred through the ritual, with nature through knowing what to do, and with each other with the oral word, the one that weaves relationships, individual examples and the possibility of sharing experiences in a world where we are all interwoven threads and stitches. We reciprocate when we do not impose, control, or dominate, but when we allow, respectfully, the expression of the other, to understand and feel in which place and time we weave together, without ceasing to be ourselves, now as jaqui: partner, community. The whole process of conversing, reciprocating, and becoming harmonically complementary can be consider as a mutual upbringing, were we raise to be raised, which implies ethics and aesthetics; ethics that imply reciprocity, respect, and the wisdom of upbringing; aesthetics that are clearly embodied both in the Law of Origin and in the thought and culture, which is all the shapes that we give to the world when we recreate it in diversity: weaving of threads, weaving of agriculture, weaving of irrigation, weaving of paths, weaving of houses, operating centers, temples and huacas (ceremonial centers), weaving of ceramics, sculptures, metal objects, clothes, songs, words; weaving of water.

Water the being:

Water is female when it is the liminal portal between worlds: the sea as Mother Cocha, and also the calm lagoons and the water deposits; or when it inhabits the caves where it goes deepens. It is masculine when it is ice and snow, in the apus or mountains, condensed at the glaciers of water that allow the flowing of the rivers and streams, connecting water that ultimately reaches the mother-sea. From the deep caves it emerges again as a female seed cloud, which rises to the celestial world in the calendar spiral.

Water is, therefore, from the native Andean vision, part of the community of nature with which we share life, origin, the duality of who we are, needed complementarity, mutual upbringing. For this we need to understand that it is not an object, mere H2O (the dull vision of the flesh, in which we lose the heart and soul of things), a simple resource to be controlled, used, and accumulated according to individual interests, but rather a brother or a sister (depending on the manifestation it has in shape and energy), with whom we share a common destiny in this experience in the part earthy world, a part of it is to learn to establish a dialogue in reciprocity that allows us to become complementary so that we can raise up each other. Then, we will know how to relate with each other.

Fertilizing water moves in different cycles of the space-time (pacha). We have already mentioned a macrocycle that encompasses from Milky Way to the underworld, making its planetary and cosmic circulation. But the water being, the water person, also has particular cycles of manifestation: continental, regional, in each local pacha. This is why dialogue has different levels and the observation different landscapes and scopes. Conversation takes place with the weather and its signals to understand the type of crop year that will come regarding water: drought, regular rainfall, flooding; with the time of the year for the agricultural cycle and the expansion of water: fallow, soil preparation, sowing, weeding, irrigation, fruiting, harvest, and storage; with the purely local pacha in the ayllu or community and with regard to other communities and to the archipielago territory (located in different ecosystems and climate zones) to ensure food security; thus, a unity-complementarity is woven within the diversity that makes it possible. It is through this conversing and reciprocity where multiculturalism in the dialogue with ecosystem multi-diversity is understood, experientially.

Water, though, does not exist on its own, it is family with nature and provider of structure to the territory. Other level of conversing and reciprocity is established within this first family in the community of nature: among plants, animals, earth, wind, water, fire, movement (the five elements), who converse with each other and with human beings. In the field water is in a state of dialogue and ayni (reciprocity) with the specific soil where it resides and walks, with the harvests that grow there as a family weaving, with the animals that live in this environment, and with the natural and recreated microclimate of the field. It is all a living weaving of wefts and weaves in cycles of expansion-contraction complemented at the chakana. When the human being converses with the field and thus with the water, he/she does it through the ritual and his knowledge, including the sun, the stars, the clouds, the ray, the hail, the rain, the frost, the soft or hurricane force wind, the water that irrigates or floods, the drought, the plants and animals, the underworld, the celestial world with all its deities, such as the sacred and snow-covered hills.

The human being must learn to observe this inter-community dialogue expressed in the visible signs of what can happen; then he/she must converse with this family-field and establish his/her reciprocity between communities. For this reason every level of mutual upbringing begins with the ritual, the highest dialogue that enables every relationship, going from gratefulness to petition. The dialogue with nature and with water as a being is given through ritual, through the language of observation, memory, and through doing, which is implementation and experimentation. Finally, the human community converses with one another to understand how the experience of each, in their personal pacha, can be combined with that of the others and how the example of some allows a better understanding for the rest. There is not a criteria of a truth that is absolute, abstract or superior in authority, but the wisdom of understanding the diverse weavings that can be combined in warps of understanding the processes in their different cycles and levels. The hegemonic is not important, but the similarities that we share.

In this order of things related to water, the living female and male being, with body, heart, energies, character, feelings, and culture, the way in which she/he wants to be raised must be respected to allow, in reciprocity, a good breading of the nature and the human. For this reason it should be impounded only when it is necessary, channeled when she indicates it, accumulated temporarily for the common good. Like every energy, when it is retained and accumulated for no reason, it decomposes; when one wants to monopolize and corrupt, it bursts; all living energy must flow through the weaving connecting the parts of the system in a planetary body. Mama Cocha as the sea, lagoons, puquios, streams and rivers, ice and snow, are beings that are conversing, offering all their wisdom, and also learning from one another. The key of this relationship between communities and water is that in the Andes everyone is attuned with the world as it is, to understand it and raise oneself, not to use it and transform it. The health of a community depends on the other two; either the deities, nature, and human communities are healthy, or health is precarious, for it cannot be fragmented.

In this process of mutual breeding, knowing and understanding are given through a dialogue and reciprocity in the action itself, were the territory and the field, water in all its expressions of form and energy, the three communities together, are the true classroom. One learns by observation and example, by sharing the experiences and taking each action by one’s self, to contribute with one’s own experimentation and recreation of reality, in accordance with the cosmovision and the thought which are the warp of one’s community, its main identity.

The water, living and vivifying being, is still waiting, in this mestizo and desecrated world, that we remember the principles of conversing and reciprocity, the ways of mutual breeding, seeking to restore order. Because all order begins within each one of us, within our own elements, to be able to interact coherently with these element-beings in the great body of the Mother.